The Science of Vampirism

Extended Edition: Part II

By Robert LomaxOrigin & Evolution

|

| Early human migration across the Red Sea. |

The actual evolution of the human vampirism virus is difficult to comprehend, since viruses are far too small and fragile to properly fossilize. However, judging by their similar structures, it's believed that HVV and rabies share a common ancestor—not unlike apes and humans.

HVV probably started off identical to rabies before mutating into a virus more similar to HIV and HPV, which alter cellular DNA. As detailed before, HVV bears the following differences from other viruses: it can infect and replicate in cells without destroying them, infect many different types of cells, and complete its incubation period in less than 24 hours. It's also the most logical order in which the virus evolved these characteristics. Most viruses to this day are no more advanced than they were thousands of years ago because they still haven't learned to stop killing the cells they infect. This is perhaps HVV's greatest evolutionary achievement, as it set the foundation for many beneficial mutations to occur. Infection of the entire body was another important step, as it would prevent rejection of mismatched tissue. From there, infection of the thyroid gland resulted in faster replication.

Despite these accomplishments, the virus would still need to go through a long and rigorous refinement process in order to correctly "rewrite" all the cells they infect. Early proto-vampires were most likely mindless, feeble and short-lived—riddled with cancer, tissue necrosis and immune disorders before natural selection weeded out the failures. Non-human mammals provide some proof of this, as they'll display these very symptoms after transformation, and generally die within a week. The virus has no effect on non-mammalian species, although they can still become short-term carriers before the virus dies in their system. The only known long-term carrier is the aforementioned bat flea.

No intact or discernible fossils of vampires older than 10,000 years have ever been discovered, unfortunately, leaving only these educated guesses regarding their evolution.

Stages of the Disease

|

|

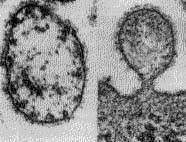

Electron micrograph of HVV (left). The virus budding off an infected cell (right). |

|

|

In 1800 France, an infected woman is given a transfusion of goat's blood— a desperate, futile measure to ward off the disease. |

|

|

During vampire epidemics, many victims were buried while still in a vampiric coma. |

Additional Symptoms

|

|

Vampire vaccine in an earlier incarnation. |

Unfortunately, hospitals in the United States no longer carry stores of the vaccine. The remaining supply is locked away in an underground vault at the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta, Georgia. The decision to store the supply came in 1963 after U.S. officials deemed the threat from vampires to be over. There was also concern over the safety of having vaccine accessible at hospitals, since in rare cases it can actually cause vampirism.

If you feel you have contracted HVV, then you should head to the nearest hospital straight away, and hope for the best. If you were bitten by an animal, tell them that the symptoms showed up within several hours so they can rule out rabies and other diseases. If it was a vampire, show them the bite wound and describe what the attacker looked like: pale skin, bloodshot eyes and dilated pupils should suffice. Do not mention vampirism, because you'll just sound crazy. Hopefully they'll call the CDC and convince them to fly the vaccine out to you in time. The closer you live to Atlanta, the higher your chances will be. If you're lucky enough to live in Atlanta, then you should definitely head to the CDC instead of a hospital.

|

|

HVV patients were typically restrained during their treatment and recovery. |

Systemic: High fever, with moderate to severe chills. Viral infection of the thyroid gland increases metabolism for the purpose of faster replication. Drying of the tissues, dilated vessels and weight-loss are some of the more prominent metabolic symptoms, and can be potentially fatal if the victim becomes overly dehydrated or malnourished. Hormones secreted by the infected cells can also cause symptoms such as acne and heavy menstruation. During the coma, fever is dangerously high and persists for roughly 12 hours, before dropping sharply into room temperature.

Eyes: Inflammation, watering and blurred vision. Pupils become fully dilated during the coma.

Ears: Dryness, itching and aching in the outer ear, with aching and congestion in the tubes of the middle ear.

Nose: Sneezing and congestion with clear discharge.

Mouth: Dryness and chapped lips; inflammation of the oral mucosa, with possible ulceration.

Throat/Lungs: Dryness, coughing, soreness and inflammation, with possible ulceration of the esophagus. Moderate to severe inflammation of the lungs during the coma, which can be fatal.

Skin: Dryness, itching, flaking and possible cracking; flushing, with redness around the eyes, nose, mouth and throat; excessive sweating, with possible acne and hives in places covered by clothing. During the coma, some degree of acne and hives will appear on the victim's back and buttocks, as well as the backside of their shoulders, arms and legs if they're laying completely flat.

Brain/Nerves: Headache, dizziness and general discomfort; hypersensitivity to stimuli such as light, sound and touch; insomnia, mood swings and irritability, with possible auditory hallucinations. Dementia, tingling, numbness, loss of motor control and partial paralysis shortly before the coma. Moderate to severe inflammation of the brain during the coma, which can be fatal.

Muscles: Fatigue, weakness and joint pain, with shivering due to chills, and minor spasms in the extremities. During the coma, these spasms become more synchronized, allowing blood flow to continue even after the heart stops.

Heart: Increased heart-rate, with high blood pressure and possible palpitations. Can be potentially fatal for those with pre-existing conditions. Moderate to severe palpitations during the coma until around the halfway mark, when the heart slows and cardiac arrest sets in.

GI Tract/Bladder: Extreme thirst, loss of appetite and frequent urination; nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain with possible bloating, excess gas and diarrhea (depending on food contents); moderate to severe acid reflux and inflammation of the stomach lining, with possible ulceration.

Liver/Spleen: Moderate to severe swelling and inflammation with concurrent abdominal pain and fluid bloating, all of which can be easily confused with the GI symptoms. This interference with their normal functions also causes a gradual buildup of the waste product bilirubin in the victim's bloodstream and extracellular fluid, causing the skin and the whites of the eyes to develop a sickly yellow coloration during the coma stage.

Blood/Vessels: Viral interference with the liver, bone marrow and vessel lining causes a temporary reduction in clotting factors and coagulation. As a result, the hyper-dilated vessels will leak more easily, causing the skin to bruise and the victim to cough up, vomit and excrete blood, with possible hemorrhoid formation. Mild bleeding from the eyes, nose, gums and sweat glands may also occur as well, either during the coma or just before it hits. If the victim is susceptible to strokes, then this can be potentially fatal.

Lymph Nodes/Vessels: Moderate to severe swelling and inflammation, causing the neck to appear lumpy or enlarged.

No comments:

Post a Comment