The Science of Vampirism

Extended Edition: Part VI

By Robert LomaxBody Temperature & Dormancy

|

|

Seen through thermal vision, a vampire attacks its prey. |

Although warmer weather makes them feel more energized, vampires can't handle temperatures past 100 for more than a few minutes without overheating and possibly dying—especially since they can't sweat much. They'll dive into water to cool off, but will avoid it like the plague at colder temperatures. In fact, diving into a large body of water is one of the better ways to escape from pursuing vampires. That's not to say they won't attempt to follow you into the water, but if you can stay out far enough and long enough, they'll hopefully consider you more trouble than you're worth.

|

| A vampire's cold feet on a heating pad. |

If vampires did in fact live during the last ice age, then it makes perfect sense why they would develop an immunity to freezing. For more information, see the 1942 case titled Vampires on Ice.

If food is scarce, or if the situation is less than hospitable, vampires are also able to go dormant and hibernate voluntarily, provided they can find a safe place to construct a lair. Abandoned buildings, mines and caves are high on the list of potential lair sites. Once safely ensconced, the vampire will fall into a deep sleep, during which its bodily functions slow to a level just enough to sustain it. The longer a vampire hibernates, the more dried and withered it becomes as its body uses up nutrients. In time, it may resemble a mummified corpse, which can be dangerously deceiving to whomever may discover it.

Unlike bears and other hibernating animals, a vampire can quickly snap out of its dormancy in full attack mode. Still, they are much easier to sneak up on while in the dormant phase. The outer limits of this dormancy phase have yet to be discovered, although FVZA scientists in the 1940s and 50s observed vampires remaining in the dormant phase for over 10 years. In 1964, a construction crew in London uncovered a vampire that had been dormant since 1688—almost 300 years—although it was quite lethargic and barely able to move.

Reproductive Organs & Sexuality

|

|

What little sperm that can be harvested from vampire testes is always highly deformed. |

Aging & Life Expectancy

Because they presented such a danger to society, most vampires were destroyed long before the outer limits of their lifespan were determined. Ancient history offers some clues, however. In Ancient China, there was said to be one vampire in the Emperor's court through the entire Eastern Zhou Dynasty, which would put his age at 550. More accurate modern records have certified vampires of over 300 years old.

|

|

Chromosomes (purple). Telomeres (pink). |

|

|

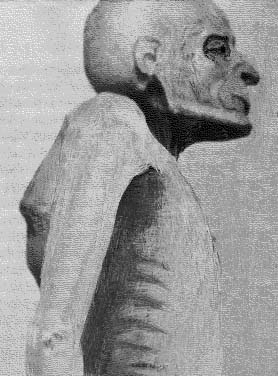

A 125-year-old vampire photographed in Spain; 1901. Note the curved spine, lack of hair and emaciated frame. |

Though their DNA may have the ability to resist aging, mutations that take place during the initial coma cause a vampire's appearance to change dramatically within the span of a decade. It will lose all of its hair as its fat and water stores shrink away, causing its skin to become thinner and more transparent. This gives it a distinctly withered and dried appearance, with smaller muscles and a pronounced curvature of the spine. Once that period is over, however, they'll generally look and perform the same way over many years—as long as they can avoid disfiguring or debilitating injuries, of course.

|

| Five vampires at an FVZA facility in 1918. |

|

|

Elmer McCurdy, an Oklahoma outlaw who was turned in 1911 at age 31. The second photo was taken after his sunburnt body was found hanging from a tree in 1959. He had also filed his fangs down and inserted needles into his flesh. |

It's also worth noting that the growth of an underage vampire becomes permanently stunted upon transformation, while an elderly vampire will always bear an aged, wrinkled appearance.

Cross-Species Infection

|

| A rabid canine. |

Unlike vampires, non-humanoid coma survivors do not experience dental growth, and are completely rabid from brain swelling. Cancer, tissue necrosis and immune disorders occur as well, and also shed light on how early proto-vampires may have started out. One reason for these problems is that not as many cells can be infected and transformed, causing tissues to become mismatched and identified as foreign by the rest of the body. In addition, some degree of viral production will continue even after the coma, which only causes further cell destruction. This biological incompatibility with the virus is always fatal: the vast majority of primates live less than a week; non-primates even sooner.

The virus' effect on animals raises an important question: why us? Why is the virus so much more compatible with our bodies? After all, the rabies virus doesn't treat us any better than other mammals. While it's perfectly plausible that millions of years of natural selection could craft the vampires we know today, it would require relatively constant exposure, death and re-exposure to weed out the problems seen in other animals. As disturbing as it is to consider, vampires could have very well been bred like dogs.

No comments:

Post a Comment